Medial collateral ligament

Knee ligament sprains or tears are a common sports injury.

Your knee ligaments connect your thighbone to your lower leg bones. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) are found on the sides of your knee.

Athletes who participate in direct contact sports like football or soccer are more likely to injure their collateral ligaments.

Anatomy

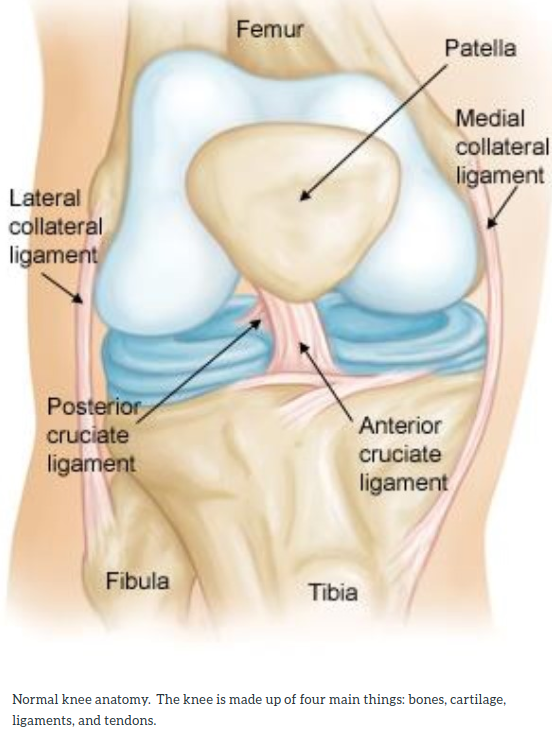

Three bones meet to form your knee joint: the femur (thighbone), the tibia (shinbone), and the patella (kneecap). The kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some protection.

Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

Collateral ligaments. These are found on the sides of your knee. They control the side to side motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

- The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is on the inside. It connects the femur to the tibia.

- The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is on the outside. It connects the femur to the fibula (the smaller bone in the lower leg).

Cruciate Ligaments. These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an X, with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the front and back motion of your knee.

Description

Because the knee joint relies on just these ligaments and surrounding muscles for stability, it is easily injured. Any direct contact to the knee or hard muscle contraction — such as changing direction rapidly while running — can injure a knee ligament.

Injured ligaments are considered sprains and are graded on a severity scale.

Grade 1 Sprains. The ligament is mildly damaged in a Grade 1 sprain. It has been slightly stretched but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

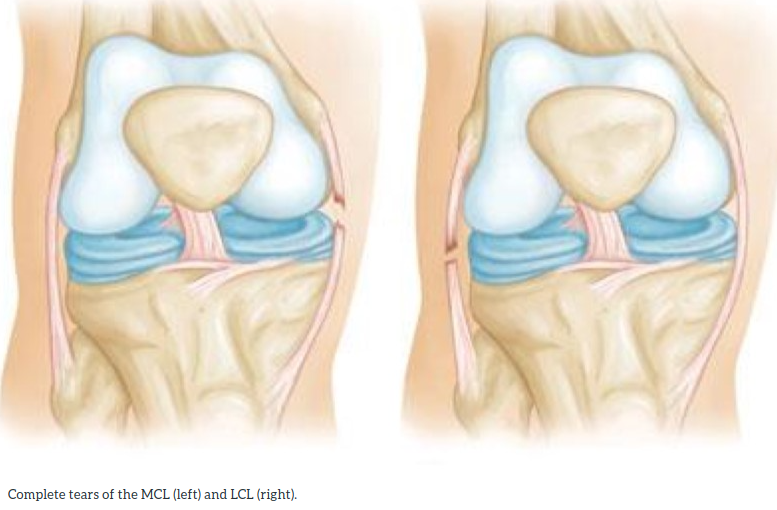

Grade 2 Sprains. A Grade 2 sprain stretches the ligament to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

Grade 3 Sprains. This type of sprain is most commonly referred to as a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been torn in half or pulled directly off the bone, and the knee joint is unstable.

The MCL is injured more often than the LCL. Due to the more complex anatomy of the outside of the knee, if you injure your LCL, you usually injure other structures in the joint, as well.

Cause

Injuries to the collateral ligaments are usually caused by a force that pushes the knee sideways. These are often contact injuries, but not always.

Medial collateral ligament tears often occur as a result of a direct blow to the outside of the knee. This pushes the knee inward (toward the other knee).

Blows to the inside of the knee that push the knee outward may injure the lateral collateral ligament.

Symptoms

- Pain at the sides of your knee. If there is an MCL injury, the pain is on the inside of the knee; an LCL injury may cause pain on the outside of the knee.

- Swelling over the site of the injury.

- Instability — the feeling that your knee is giving way.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination and Patient History

During your first visit, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and medical history.

During the physical examination, your doctor will check all the structures of your injured knee, and compare them to your non-injured knee. Most ligament injuries can be diagnosed with a thorough physical examination of the knee.

Imaging Tests

Other tests that may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. Although they will not show any injury to your collateral ligaments, X-rays can show whether the ligament tore off (avulsed) a piece of bone when it was injured.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. MRI scans create better images of soft tissues, like the collateral ligaments, than X-rays.

Treatment

Injuries to the MCL rarely require surgery and are often treated with a hinged brace.

If you have injured just your LCL, treatment can be similar to an MCL sprain, but surgery may be recommended, especially in cases where the ligament has pulled directly off the bone. If your LCL injury involves other structures in your knee, your treatment will address those, as well.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Ice. Icing your injury is important in the healing process. The proper way to ice an injury is to apply crushed ice directly to the injured area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, with at least 1 hour between icing sessions. Chemical cold products (blue ice) should not be placed directly on the skin and are not as effective.

Bracing. Your knee must be protected from the same sideway force that caused the injury. You may need to change your daily activities to avoid risky movements. Your doctor may recommend a brace to protect the injured ligament from stress. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

Physical therapy. Your doctor may suggest strengthening exercises. Specific exercises will restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it.

Surgical Treatment

Most isolated collateral ligament injuries can be successfully treated without surgery. If the collateral ligament is torn in such a way that it cannot heal or is associated with other ligament injuries, your doctor may suggest surgery to repair it. Your surgeon will discuss which tecnique of repair is best for you.

Return to Sports

Once your range of motion returns and you can walk without a limp, your doctor may allow functional progression. This is a gradual, progressive return to sports activities.

For example, if you play soccer, your functional progression may start as a light jog. Then you progress to a sprint, and eventually to full running and kicking the ball.

Your doctor may suggest a knee brace during sports activities, depending on the severity of your sprain.